Apparel Industry Deep Dive Part 2: The Social Cost of Fashion

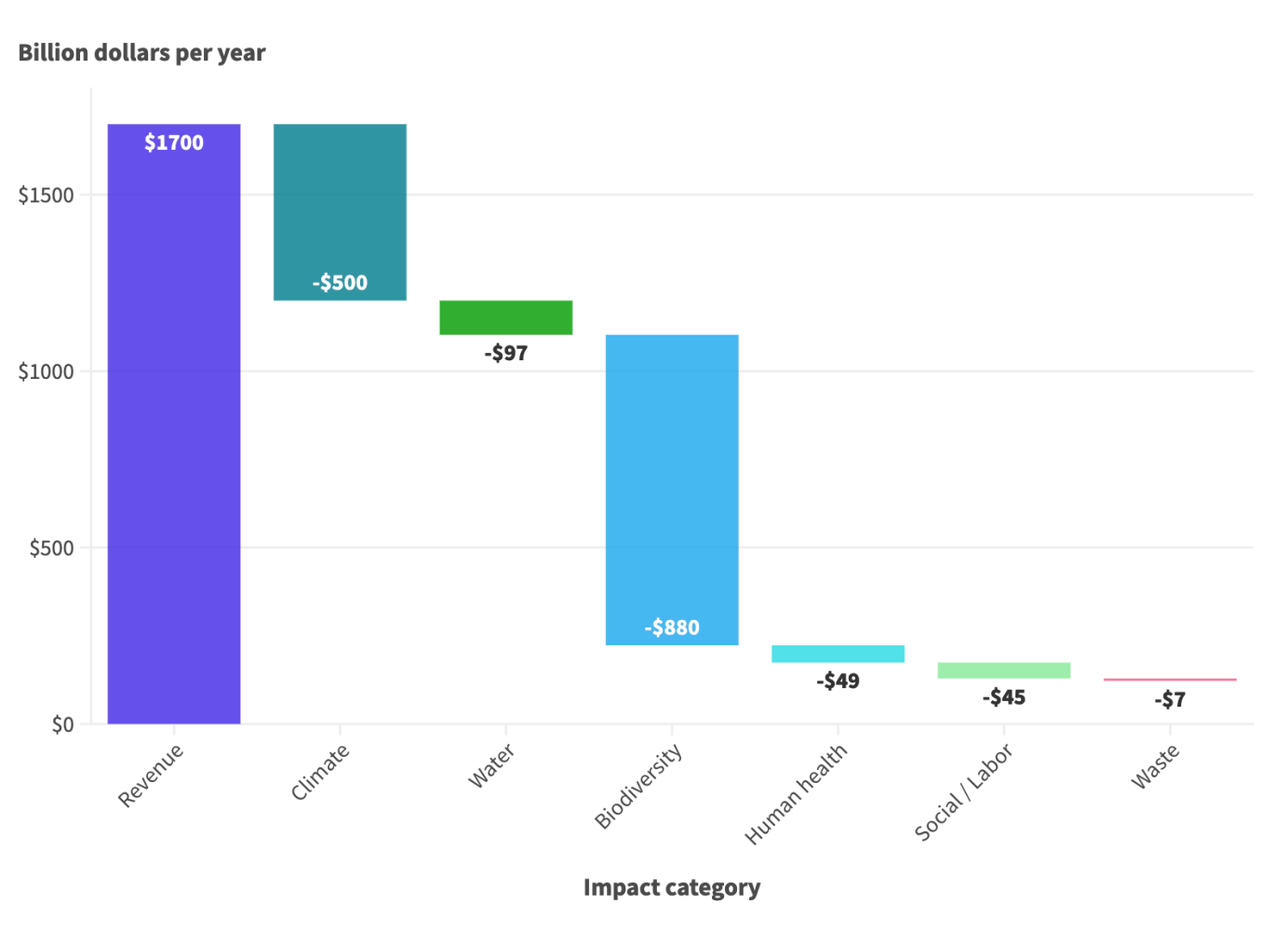

In Part 1 of this series, we showed that the environmental harms (greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution, and biodiversity loss) associated with the global apparel industry cost humanity at least $1.5 trillion per year. That's a lot considering that the annual revenue of the industry is $1.7 trillion, and we aren't even done yet. Now, let's look at the social harms of fashion.

Human health impact

Our health, of course, depends on climate, water, and biodiversity. However, we will look specifically at the human health impact associated with the production and use of apparels.

Improving chemical management to reduce occupational exposure during textile processing can result in a value opportunity of €7 billion ($7.5 billion USD) per year by 2030. Thus, the human health impact from apparel production is at least $7.5 billion per year.

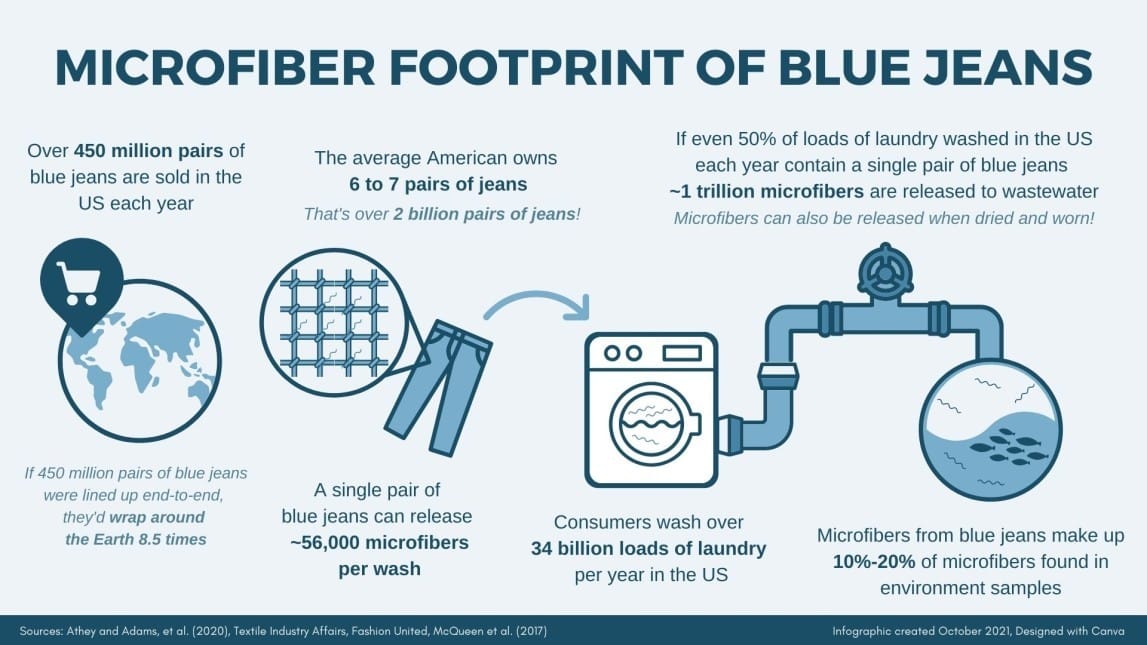

Plastic microfibers and chemicals (e.g., per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as “forever chemicals”) are released into the environment when we wash our clothes and can pollute our soil and drinking water. Furthermore, dyes and other chemicals in clothes can affect the health of the wearer, as in the case of flight attendants who got sick from their uniforms.

Not much data is available on the human health impact of clothes, so we need to make some assumptions. The disease burden on Americans from PFAS exposure is estimated to be $5.5–63 billion per year. Let’s take the average: $34 billion per year for 330 million people. If we extrapolate this cost to a global population of 8 billion people, that would be $830 billion per year. Let’s say that clothing accounts for only 5% of the PFAS burden—because adsorption through the skin is not a significant exposure route for PFAS—that would be $42 billion per year globally.

The fact that not every person in the world has the same PFAS exposure as an average American (so the estimate should be adjusted downward) is compensated for the fact that we haven’t accounted for illnesses caused by all the other chemicals in clothing (which would raise the estimate). For now, we will say that the disease burden due to toxic chemicals in clothes is $42 billion per year.

Together, the human health impact from apparel production and use globally is likely to be at least $50 billion per year.

Unjust labor practices

The clothing, textile, and footwear industries together employ more than 60 million workers around the world. Most workers are not paid a living wage, and the average gap between minimum wages and living wages in garment-producing countries is 45%. One analysis suggested that the value opportunity of “not further increasing the number of workers being paid less than 120% of the local minimum wage while maintaining the projected growth of the industry” would reach €5 billion ($5.4 billion USD) per year by 2030. We need to double that estimate (so around $11 billion per year) to get close to the living wage.

Garment workers spend long hours in factories that may not have adequate health and safety measures in place. Aside from occupational exposure to hazardous chemicals, workplace injuries also need to be considered. It is estimated that the externality, measured as the value opportunity of eliminating workplace injuries in the global apparel industry, would reach €32 billion ($34 billion USD) per year by 2030.

The total cost due to unjust labor practices in the global apparel industry is about $45 billion per year.

Waste production

As mentioned in Part 1, ~100 million tons of fashion waste is landfilled or incinerated per year. One analysis used a value of €66 ($71 USD) to represent the externality of a ton of waste, including effects such as emissions from decomposing waste (methane) and waste incineration (greenhouse gases, air pollutants) and the effects of landfills and incineration sites (noise, dust, litter, odor, vermin, visual intrusion). Multiplying 100 million tons and $71 per ton gives us $7.1 billion per year for fashion waste that is landfilled or incinerated.

There are other nuances regarding waste. Much of the clothing that is donated in high-income country ends up being resold in sub-Saharan Africa. The trade of 4 million tonnes of used textiles in second-hand markets in Africa provides employment for millions of people, but they have led to the collapse of the local textile manufacturing industry, as locally-made clothing cannot compete with the cheap second-hand clothing from overseas. Furthermore, the quality of clothing has gone down thanks to fast fashion, and 40% of the shipments is essentially textile waste. Therefore, clothing waste disproportionately affects the environment and livelihoods of people in the Global South. The economic burden of these effects is much harder to quantify. All we can say here is that the true cost of fashion waste is likely to be much higher than $7.1 billion a year.

Cumulative externality

Summing the costs across different impact categories, we get a cumulative externality of ~$1.6 trillion per year for the global apparel industry. That is about as much as the annual revenue of the industry.

There are undoubtedly other externalities that we did not cover in this analysis, so the total externality may be much more than $1.6 trillion per year. Moreover, our calculations are only as good as the accuracy of the data and assumptions used. If you know how we could improve our analysis, please send a message to stephanie.lau@theidi.org.

Now that we have done an inventory of the environmental and social harms of the apparel industry, we can think about solutions for reducing those externalities. We will cover some of the potential solutions in Part 3.

Comments ()